150th anniversary of the death of Dom Prosper Guéranger

Homily preached by Abbot Xavier Perrin of Quarr Abbey at Solemn Mass at St. Cecilia’s Abbey on 30 th January, 2025 to mark the 150 th anniversary of the death of Dom Guéranger (1805-1875).

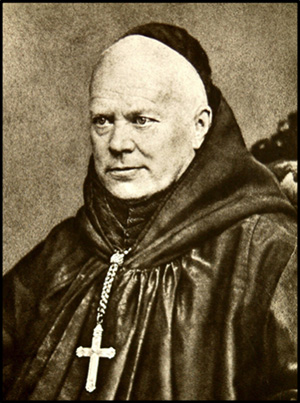

Dear Brothers and Sisters in Saint Benedict. There was a man of venerable life, blessed by God, whose name was Prosper Guéranger. He was not tall, had a round face, beautiful eyes and a lovely smile – a bit like you, dear Abbot Cuthbert. He had an outstanding knowledge of the Liturgy of the Church– very much like you, dear Abbot Paul. Last but not least, he was French – like me, I am afraid. We need at least the three of us to make the one man he was!

Gently, and sometimes more forcefully, he was a sort of a giant, always ready to love and ready to fight. Born with his Century, he went along with it from Revolutions to Empires and from ruins to restorations: of the monastic life, of the liturgy of the Church, of the authority of the Papacy. He also went against his time: against the spirit of the Enlightenment, against Gallicanism, naturalism, and liberalism. What then did he stand for? He was rooted in the faith of the martyrs, the Fathers of the Church and the Saints. He breathed the fresh air of the One, Holy, Catholic, Apostolic and Roman Church. He felt it was his mission to provide the faithful with a direct access to the source of Truth and Love which was entrusted to Peter and his successors. For him, no better access to this treasure could be found than the Liturgy of the Church which he felt it was his mission to help as many as possible to rediscover.

This is what he did whilst remaining above all a monk and an abbot. On the day of his ordination at Tours, he visited the ruins of Marmoutiers, the monastery where St Martin liked to retire on the outskirts of his busy episcopal city. There he felt inspired to sing the Rorate. As he came to the last stanza, Consolamini, he had the sudden intuition that monastic life would once again flourish in France after its total suppression by the Revolution. He had been brought up in a lower middle-class family in Sablé, not far from the derelict buildings of the Benedictine priory of Solesmes. He could think of this modest house as a place where the Benedictine venture could begin again.

Now, was he a Romantic filled with nostalgia for idealised Middle Ages? No. He was a historian who had learnt to value the contribution made by monasteries to the life of the Church over the Centuries. He knew their role in cult and culture, education and mission. He saw the thousands of abbeys and priories which had spread all over Europe as houses where the prayer of the Church was unceasingly offered for the benefit of the People of God. He perceived clearly that monastic life is an integral part of the life of the Church. It belongs to its fullness. It is essential to its identity, for the Church is, first and foremost, the “society of divine praise”, as he said in his last opuscule – or, to put it with the words of Vatican II, Christ’s “beloved Bride who calls to her Lord, and through Him offers worship to the Eternal Father” (SC 7).

He grew as a monk at the same time as he grew as an abbot. Although he enjoyed a short novitiate in Italy, he learnt monasticism by living out the life according to the Rule and by introducing others to it. The Rule of St Benedict made him the Benedictine he became. He was able to read it within the tradition of the Church, from Cassian to St Bernard, from Peter the Venerable to Mabillon, from St Gregory to St Gertrude and St Mechtilde, Louis de Blois, Dom Claude Martin, and even Dom Augustine Baker.

His was not a quiet journey in a peaceful countryside. He met with difficult situations and difficult people. Always penniless, he had to beg for his monastery all his life. He founded four monasteries of men (Paris, Acey, Ligugé and Marseilles) of which two only worked out well. The foundation of the convent of Sainte Cécile de Solesmes was the consolation of his final years, and like a seal on the contemplative orientation of his monastic work.

He had dreamt of resuming the academic studies of the St Maur Congregation, but very few of his disciples were up to the task. Instead of scholars, he was sent ordinary men. He welcomed them with his fatherly warmth. Gently and joyfully, he initiated them into a regular enclosed life which, faithfully lived out, produces fruits of genuine conversion and humble contemplation. There was something authentic in the Benedictine life as it was lived at Solesmes. From Germany and Italy, from Austria and even from England – think only of Dom Lawrence Shepherd – monks and nuns came to Solesmes wishing to prepare themselves for new foundations or to revisit their own Benedictine tradition.

He taught a lot. He wrote many books and articles. He often travelled. He was one of the key figures of the Catholic renewal in French nineteenth Century. Above all, he kept his joy and his balanced view of life. He went swimming in the Sarthe when he could and did not disdain to teach Catechism to the children of his neighbours among whom he had many friends. Strongly worded when it came to countering people who had different views, he proved remarkably kind and patient towards ill-balanced monks, prudent and loving in spiritual direction, and always generous to the poor. When he died, 150 years ago, these were seen crowding the little abbey church of Solesmes to express their gratitude to the good Abbot who had so often helped them.

Dom Guéranger visited England once in 1860. He met with many famous Catholics such as Faber, Manning, Newman, and Ullathorne. He visited Ampleforth, Stanbrook, and Downside, and attended the consecration of Belmont Abbey Church. His disciples arrived at Farnborough in 1895. Some of the monks who knew him are buried at Quarr and, of course, his greatest disciple, Madame Cécile Bruyère, died in this monastery in 1909. His sons and daughters are present in 30 monasteries in 3 continents. The cause for his beatification has recently been officially reopened. He remains a great master of monastic life and his example of a life totally given to the service of Christ in the Church is an inspiration for many. We can certainly welcome him as a father in monastic life, a master who will help us become ever more what we are called to be: disciples of St Benedict in and for the Church today.