The Isle of Wight to Solesmes – 1922

Return of Benedictine monks

Written by Fr. Gregory Corcoran OSB

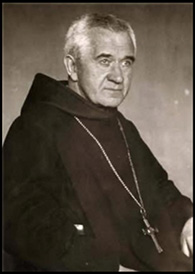

This year marks the centenary of the return of the monks of St Pierre and the nuns of Ste Cecile to Solesmes after their twenty years on the Isle of Wight. This was a result of the national unity achieved in France during the First World War. Politicians continued to express their awareness of the benefits that this unity conferred on their country, thereby encouraging the new Abbot of Solesmes, Dom Germain Cozien, to prepare for the return of the community from their exile. One of the difficulties arose from the intransigent opposition of his predecessor, Abbot Paul Delatte (picture), to monks enlisting in the armed forces. Dom Delatte had two serious reasons for his opposition.

Firstly, Canon Law forbade clerics to kill for any reason. Secondly, unjust laws had made it impossible for religious orders to function normally in France, and caused thousands of religious to go into exile. The regime had no right to ask those it had driven into exile to sacrifice their lives in its defence. Other superiors looked on things differently, which meant that Solesmes had singled itself out and appeared unpatriotic to some people.

The political situation in which Dom Cozien had to operate was complex. He was subtle in exploiting the points in his favour, stating his community had not been refused authorisation to remain in France, nor had it been expelled. This was entirely true, as they had left France freely without asking for authorisation, believing they had a perfect right to practice their religion without any ‘by your leave’ from anyone. This simple principle guided Dom Cozien throughout the process of the return to the monastery which he himself had never seen. They had left without seeking authorisation to exist; they would return in the same way. Backed by Pope Benedict XV, Dom Cozien held onto this position unflinchingly in spite of the advice of everyone else, including the Papal Nuncio in Paris, the Bishop of Le Mans, and the Marquis de Juigne, who was the legal owner of the monastery. He simply stated that the monks were returning to their home to pray and study, encouraged by the statements of the leaders of the country that all Frenchmen should live together to rebuild their national life. It was one of the tricks of history that the minister, Aristide Briand, who had steered the legislation through the Chamber before the Great War was President of the Council of Ministers in 1921.

In October 1921 he made a long discourse proposing moderation, but concluded, for the sake of the hardliners, by saying that reactionaries must not have a free hand. He won a large majority, but the following January his government fell.

While Dom Cozien was guided by his conviction that God’s will lay in the immediate return of the community to Solesmes he had a loyal and energetic lieutenant in Dom Noetinger, his bursar. In view of the complexity of the practical difficulties his presence was an appropriate gift of Divine Providence.. The great abbey on the banks of the Sarthe had been sold a few years before the Great War to a local magnate, the Marquis de Juigne, who had leased it for the duration of hostilities and the two years following to the Medical Service of the French Army. Although the old Priory building had housed the staff and administration and was in reasonable condition the great new building had housed the patients, who had not been kind to it, nor did they vacate it until September 1921. The absence of any supply of water or electricity also made for difficulties. Even when the monks began to arrive they were dependent on rain butts for water supply within the monastery during the relatively dry winter 1921-2.

Although these problems loomed large, the greatest was the sheer quantity and weight of the furnishings of a monastery. In 1901 nothing that could be transported to England had been left behind to be confiscated by the French government. For twenty years the community had been growing and, including the twenty eight members of the novitiate, already exceeded one hundred. Hundreds of tons of household goods and church furnishings had to be shipped to Southampton and thence to St Malo. Nor should we forget the library, which was so huge that some of it had remained in cases for the twenty years of the exile. Curiously, perhaps, it was this transfer of goods that drew the attention of the French authorities to what was happening. Although the French consul in Southampton had done his best to prepare the customs officers in St Malo for what was to arrive, anticlericalism was still very much alive. The Prefect of the Sarthe was alerted by a zealous civil servant, Solesmes being in his Department, as The consignments of goods were substantially greater than a normal household would require and included quantities of church furnishings, so a zealous civil servant alerted the prefect of Sarthe, where Solesmes is situated to the possible presence of illegal religious communities. The Prefect thereupon sent the local police chief to discover the precise nature of the monastic presence of both monks and nuns at Solesmes. This was on 12th October 1922.

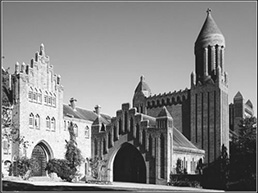

The first monks, Dom Noetinger and Frere Benoit had arrived at Solesmes (pictured above) in November, 1921, shortly after the last patients had left. They lived in spartan conditions, but the situation was not without its humour: forty five years later Frere Benoit happily recalled doing the washing up with the maid in the monastery. The titanic task of making the great monastery habitable had begun. Little by little other monks began to arrive, initially those who had served in the war, or who had been past military age, then groups of the young and able bodied who could speed on the work. The community was sufficiently large in May 1922 for regular monastic life to be resumed. Finally, on 11th and 12th October, 1922, the Solemnity of the Dedication of the Church was celebrated, presided over by the Bishop of Le Mans, Mgr Grente. A small community had been left at Quarr, but all the rest were by then installed at Solesmes.

The police chief and the bishop were thus at Solesmes at the same time. The fact that there were around six hundred of the laity present was a salutary indication to the police that the return of the monks was a homecoming, and the cause of profound rejoicing not only to the local community, but also further afield. The police chief spoke about the two communities to Dom Cozien, who assured him that the monks and nuns were intent on leading their quiet life of divine worship and study., which enabled that officer to write his report to the Prefect. Bishop Grente was aware that the next step was the crucial one: the Prefect would write to the Minister of the Interior in Paris. Everything depended on the style and content of the Prefect’s letter, so the Bishop asked for an early meeting with him. Recognising the seriously negative effects in France and beyond, of possible measures against the two communities, the Prefect drafted a letter which, while admitting that the communities were reassembling after their voluntary exile, stressed the fact that they had never been the subject of any formal intervention on the part of the civil authorities. The Prefect asserted that a request for authorisation might be expected shortly, an assertion which Mgr Grente had found it possible to countenance. In writing to the civil servants, who had been concerned about the quantities of household and church furnishings bound for his Department, the Prefect was courteously non-committal about taking matters further. In the end it was the cool determination of Dom Germain Cozien in following his clear perception of God’s will which carried the day. In more secular parlance, his success shows that fortune indeed favours the bold. There were some later moments of anxiety, as when the left wing parties won the elections of 1924, but with the passing of the years the presence of the monks came to be accepted.

Their departure from the Island had not escaped the notice of the British press; the Times of August 29th 1922 reported: The Isle of Wight is on the point of losing what a not inconsiderable number of people had come to regard as one of its most picturesque attractions. The Benedictines are leaving Quarr Abbey, which lies a pleasant half hour’s walk from Ryde, and returning to their Mother House at Solesmes, in the Departement of the Sarthe.

In conclusion it is of interest to note that the legislation against religious orders remained on the statute book until the government of Marshal Petain granted them the right to exist in France by a law of April, 1942.